Outline

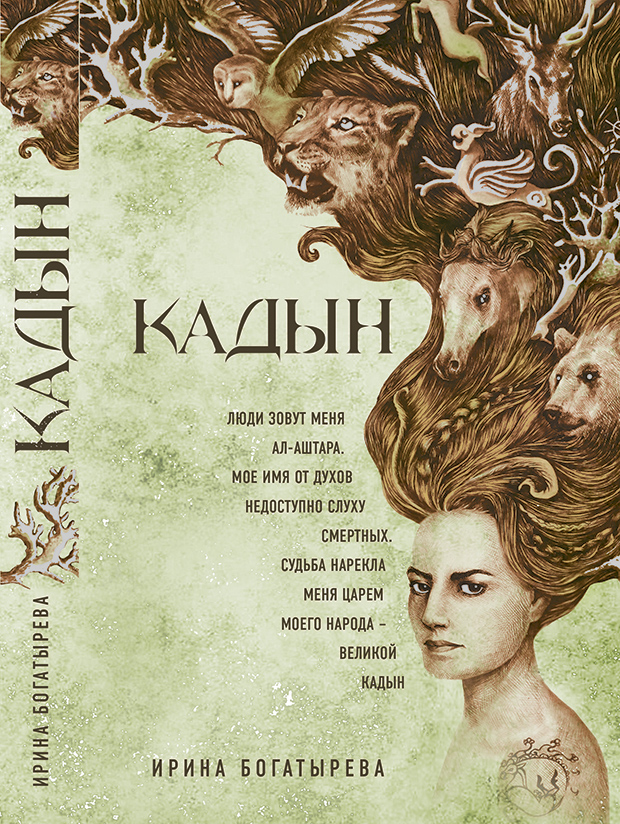

“Kadyn” (a novel)

This is a novel about the Scythians, Iranic tribesmen who in the fifth century B.C. inhabited what is now the Altai mountains. The culture of these incredible people has been occupying me for several years now. Their art, which we know from archeological findings, is stunning in its depictive precision and in the depth of its understanding of living nature. They knew how to turn clothing and the simplest everyday items into works of art that embellished the daily lives of hunters in the taiga, mountain nomads and fearless warriors.

The prehistory of this text is as follows: in 1998, the mummy of a Scythian girl was discovered on the lofty Ukok plateau in the Altai mountains. Her body was adorned with fabulous tattoos for which they called her “The Ukok Princess” The mummy was removed from the Altai Republic, and in 2003 there were several earthquakes, the most powerful of which destroyed a village. These two facts were conflated in people's perceptions and a wave of incensed demands arose for the return of the mummy to its ancestral land. She began to be called a shaman woman and the preserver of the Altai, which harkened back to the epic tale about girl warriors who protected the Altai after death. According to the legend, if both sisters are disturbed, the Altai will never again know happiness...

The heroine of my novel is the daughter of a king, a girl warrior, the priestess the cult of the moonfaced Goddess. Eventually she becomes queen herself. She is the youngest in her family and the only one in whom the ancient nomadic values, lost in her people, live on. She does everything she can, using all the power given to her, to return to them their vanished nomadic spirit, but she comes up against the kind of profound changes that even the power of a queen cannot undo. Their faith undergoes change, as does their notion of death, and from nomads whose world has no boundaries they become settled herders who guard their burial mounds of their ancestors.

But my novel is not inspired only with a foreboding of the end and of a changing people. It is filled with battles and skirmishes, with love, travels through the worlds of the shaman, the frantic ritual dances of the girl-warriors, the multicolored silks of Chinese caravans traveling the Silk Road to the West, and the pungent spices of the untamed steppes. It is full of that nomadic spirit that the queen is helpless to resist and that is the only possible source of life and creative energy for an entire people.

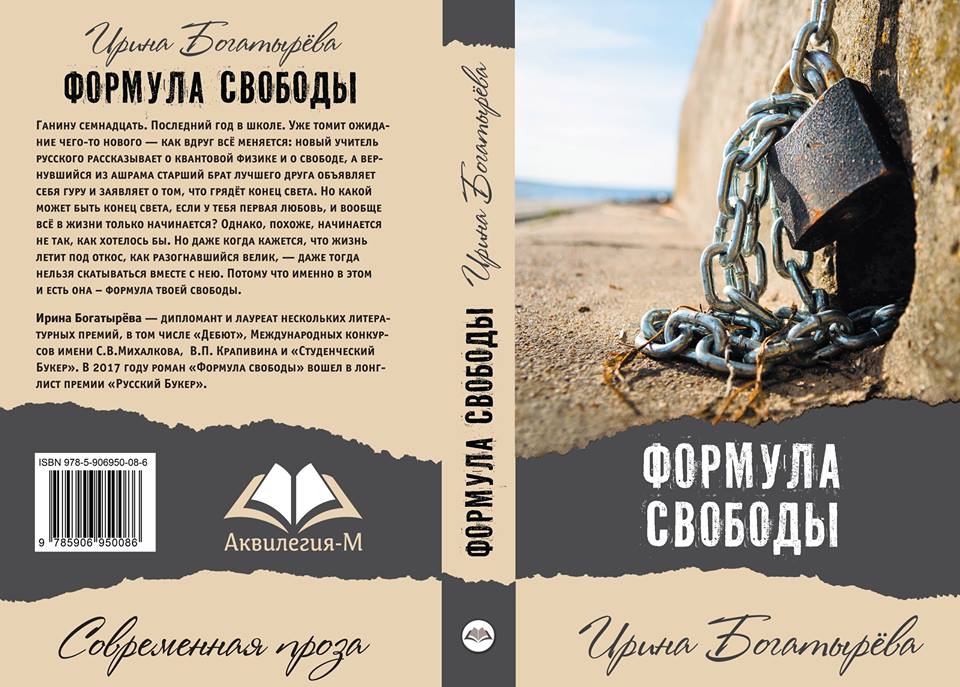

A formula of freedom (a novel)

It was 1999, the hard, diseased '90s were coming to a close. I was graduating school. It was then that my friend's brother, about whom no one had heard anything for several years already, came home to our town. It turned out that he had lived in a monastery somewhere in Siberia and he brought with him a heap of literature and knowledge that was unusual in our profoundly provincial industrial city. It was an explosive cocktail containing all sorts of spiritual teachings – from India, Siberia, South America, all spiced with a purely Russian sense of the nevitability of the impending Apocalypse. No one among us doubted that we were living at the end of days, and so all the wisdom, and also the path to salvation he offered, were received by us with the enthusiasm and zeal of neophytes.

We believed in it all – because it was impossible to be an adolescent and fail to believe in what you are told by an older, intelligent and terribly attractive friend. We gathered together, meditated, and taught ourselves to be different people, people capable of avoiding the end of the world and of saving everyone else, too. And we didn't call our group a cult, although the adults who found out about it did.

I tried to write about this for many years. And I tried to find the best way to tell about this experience. And I once understood that it may be interesting only for teens. This is the age of searching, but when you grown up you suppose to know everything about life. As a result, my novel is about teenagers and for teenagers, but with grown problems. What is the true way of living and if it exists? The characters chose different – some leave all strange ideas behind as childish delusions, some never stop fanatically believing, and some find in the jumble of ideas their own path, which they are then going to follow to the bitter end. For me, there is no one true answer. For me this is a story about people who seek and find their own faith, a life-affirming and sometimes even mystical story of revelations and false beliefs, disillusionment and first love.

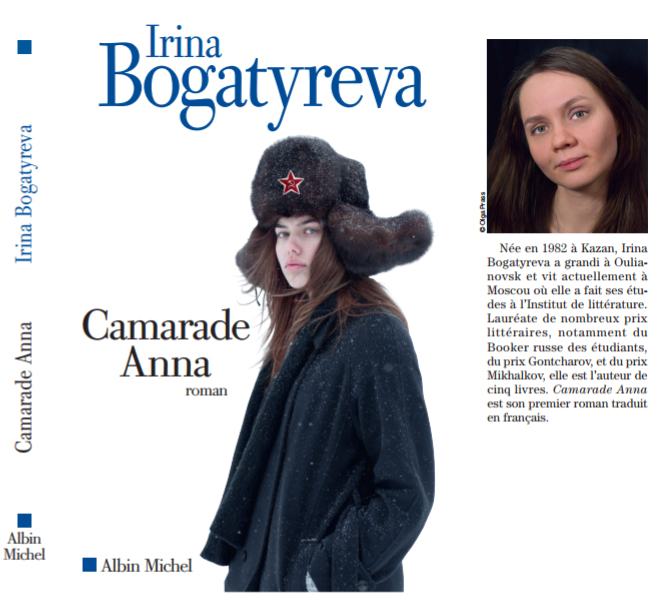

Comrade Anna (a novel)

Historical reconstructions are now a highly popular recreation in many countries. People of various ages and professions enthusiastically study some particular epoch, sew costumes sometimes no less accurate than museum pieces, participate in knightly jousts, competitions on horseback, or recreate a particular battle. It is a game in which the result is known beforehand, so something else is the important thing – the fact and process of preparation and participation.

In Russia there are clubs that reconstruction the way of life of our very recent history. But if it's easy to understand what compels people to live the lives of the 19th century nobility – if only the beauty and splendor of a ballgown! - what draws very young boys and girls to play the roles of Budenov's Cossacks, Cheka (the original KGB) commissars and members of the socialist party underground?

This is a story about one such club and about an outsider who is drawn into it by his love for “Comrade Anna,” one of its members. He strives to understand her, but he can't, because if for the others a game remains a game, Anna is incapable of studying the ideas without adopting them, of playing the role without believing in it with all her heart.

There are many Soviet cultural codes in the tale, all those things that were so often turned into fetishes or a new kind of mythology in the post-Soviet context. Even the image of the female protagonist – a fanatically devoted and ideologically defined girl, ready to forget her private life, everyday existence and family for her ideas. It is my profound conviction, however, that human psychological types do not change. And if those human types found a place for themselves in Revolutionary Russia, what place will they find for themselves in our day? At the end of the tale, Anna breaks off her relations not only with the boy who loves her, but also with the historical club in which she became what she is, and disappears in search of a genuine cause in which she can apply her ideas in real life...

Off the Beaten Track (a tale)

This is nothing more than a tale about love and the road. About youth, when you play music on the streets, when you're happy living in a commune in the company of others like yourself, young people without responsibilities, when everyone around you is still so innocent that there's no real experience to be shared. About hitchhiking, journeys and the romance of adventure.

The tale is largely autobiographical. The heroes hitchhike from Moscow to the Altai much as I once did myself. But from the day it was published, so many people saw themselves in my characters that I came to see that it wasn't my story alone, but the story of everyone who had ever experienced the joy and thrill of the open road.

Translated by John Narins

и порекомендуйте эту страницу друзьям: